Panoramic: Automotive and Mobility 2025

Search

Search

Search

Search

A resilient electricity grid underpins modern economies and is essential for almost all day-to-day activities. As global energy demand continues to evolve in the context of decarbonisation, geopolitical risk, and technological transformation (for example, increased demand for data centres, proliferation of AI, technological leaps in quantum computing, and increased use of electric vehicles), energy infrastructure has emerged as a focal point for investors and developers alike.

Recent developments have brought into sharp focus just how critical this infrastructure is, not only for states' economic security but also for national security. In the last six months, high profile examples of infrastructure compromise include a failure at a London power station that shut down the UK's largest airport (Heathrow) in March, and the sweeping power outages in April leaving millions on the Iberian peninsula without power for an extended period.

At the same time, investment in energy infrastructure is increasingly shaped by a complex web of regulatory obligations that span domestic and international regimes. Navigating these obligations effectively is critical – not only for deal completion but also for ongoing compliance and long-term operational resilience. In this article, we explore key regulatory considerations affecting energy infrastructure investment in a number of jurisdictions, focusing on national security considerations through the impact of foreign direct investment (“FDI”) regimes, and how stakeholders can navigate these inherently political hurdles to unlock value in this dynamic and strategically significant sector.

The energy sector – and indeed national governments – face what has been described as a ‘trilemma’: ensuring decarbonisation of energy production, ensuring the security of energy supply and ensuring affordability for consumers and businesses.

In response to these forces, governments around Europe have set ambitious targets for the development of new infrastructure in the coming decade but there are a myriad of regulatory hurdles to navigate. These range from planning considerations, government regulation on environmental matters, licensing issues, procurement considerations, sources of funding including state aid and subsidies, and the choice of project partners.

One of the most significant developments affecting the sector in recent years has been the proliferation of FDI screening mechanisms, aimed at protecting national security interests and public order. As energy – and more specifically, the security of energy supply becomes an ever-increasing focus for governments due to asymmetric threats from hostile actors, so too are the entities active in the wider energy supply chain and the development of energy infrastructure.

Therefore, investors and parties active in the energy sector need to consider how decisions made at an early stage of an investment might have potential national security implications in the future. At worst, governments may intervene and prevent certain actions from occurring (e.g., refusing to grant licenses after investments have already been made) or otherwise force parties to sell assets or impose conditions on how they are to be used.

In this article, we cover the energy market in the UK, France, Germany and Spain – outlining first the overall regulatory environment in each country, before considering FDI issues in more depth.

The following table gives a high-level overview of how the FDI regimes covered in this article have interacted with the energy sector to date. While there are broad similarities (e.g. energy sector transactions are subject to mandatory screening across all regimes), there are also important differences – unlike the position in the UK, investments as low as 10% or even 5% may be reviewable in the EU jurisdictions. An important common thread across all regimes, is that governments have demonstrated a robust willingness to intervene in the energy sector to protect national security and national interest. This looks set to continue.

*Lowest level of investment at which a mandatory filing may be required absent other rights (e.g. board rights)

In the UK, the energy sector has been the subject of wider regulatory reform to facilitate the development of projects of national priority. For example, the National Energy System Operator has identified 80 transmission network projects that would be required to achieve the UK’s goal of having a decarbonised power system by 2030 (“UK Clean Power Target”). This envisages growth across the range of power generation technologies, including renewables and nuclear. Notably, in order to respond to the challenge of intermittent weather-dependent renewables technology (i.e., solar and wind), a five-fold ramp-up in battery and storage capacity is expected to be required.

The regulatory agenda in respect of the electricity market in the UK is geared towards:

One key aspect of this agenda is pricing on the wholesale electricity market. The existing pricing model is based on uniform, wholesale electricity pricing which applies nationwide. Although recently there has been some debate among market actors and experts about shifting towards zonal pricing which would vary according to local factors such as demand and transmission cost, the UK government confirmed in July that it was committed to maintaining a single, national wholesale price. The government will now shift its focus to other aspects of pricing reform, including in relation to the Transmission Network Use of System charges, which will be reformed to incentivise the optimal location of new power projects.

Earlier in the year, Ofgem, the UK’s energy regulator, also implemented its “TM04+” reforms to change the way that new power generation projects are approved for grid connection. With the grid connection queue currently stretching into the 2030s, the new regime would allow Ofgem to prioritise connections for projects that are more likely to progress and align with the UK’s strategic priorities. These changes will be supplemented by further powers to manage the connections queue under the Planning and Infrastructure Bill, which also seeks to streamline the UK’s planning process as a whole.

A further feature of the UK energy debate is a renewed focus on nuclear energy, with recent decisions on funding for Sizewell C and the approval of “small modular reactors”. In addition to this, the UK and the US have signed a series of deals which are expected to boost the nuclear sector in both countries. This includes streamlining of approvals and mutual recognition of standards, alongside the announcement of a suite of deals which will provide increased market access on both sides.

However, it is worth noting that, as the graph below illustrates, despite the undisputed importance of renewable energy sources and nuclear energy, traditional oil & gas remains a key source of energy for the UK and therefore a significant area of focus for government.

For further information on the wider legal developments in the UK energy sector, please see our Future of Energy Hub here.

The UK government’s latest Modern Industrial Strategy 2025 (“Industrial Strategy”), explicitly framed economic security as a core component of national security, marking a significant development in policy emphasis. The Industrial Strategy also identified clean energy as one of the eight frontier sectors critical to the UK’s long-term prosperity and resilience and underscored the need for secure, sustainable, and sovereign energy capabilities. This policy direction shows the emphasis placed by government on protecting strategic energy assets and supply chains.

A key tool in the government’s toolbox in this respect is the investment screening regime established by the National Security and Investment Act 2021 (“NSIA”). The regime applies to qualifying investments in entities and assets, with mandatory notification required for transactions relating to specified sensitive sectors, including energy and civil nuclear. Importantly it can also screen acquisitions and investments made by UK-based businesses.

In particular, the regime covers investments in upstream oil and gas facilities, onshore processing, transportation and/or distribution of gas, onshore and offshore generation, storage, aggregation, transmission and/or distribution of electricity, liquefied natural gas import/export facilities as well as entities involved in the supply of crude oil-based fuels to UK consumers.

Under plans to refine the definitions of the sensitive sectors, which are currently the subject of government consultation, multi-purpose interconnectors will be included in the scope of the regime and a large cumulative capacity threshold based on the parties’ combined capacity will be added in relation to electricity generation. The definition of an aggregator will also be amended to be more closely aligned with that used by Ofgem.

The government, through the Investment Security Unit (or ISU) within the Cabinet Office, has broad powers to review transactions and, if necessary, impose conditions or block transactions that may pose a risk to national security, through what are known as Final Orders. These Final Orders are a valuable source of insight into the government’s concerns and treatment of energy transactions to date:

All this illustrates that understanding the NSIA regime is essential when planning transactions in the UK energy sector. Early legal risk assessment and strategic engagement with government can help address concerns and mitigate delays. The evolving nature of the regime, including through the ongoing consultation to refine sector definitions and reduce regulatory burdens, underscores the importance of staying informed.

In addition to national security considerations at the time of investment, businesses in the energy sector remain subject to close scrutiny through both sectoral regulation and broader frameworks which aim to promote fair competition and value for money for customers in the UK. Under the UK’s domestic subsidy control regime established under the Subsidy Control Act 2022, the provision of financial assistance by public authorities to enterprises (similar to the provision of assistance amounting to State Aid in the European Union), including those operating in the energy sector, is carefully reviewed. Subsidies must comply with a set of statutory principles designed to ensure that they are targeted, proportionate, and do not unduly distort competition or investment within the UK. Specific guidance applies to energy and environmental subsidies, requiring public authorities to assess the necessity, effectiveness, and potential market impact of proposed support measures. In parallel, public procurement in the energy sector is subject to the Procurement Act 2023, which mandates transparent and competitive tendering processes for certain contracts as well as the obligation on public authorities to consider excluding suppliers if there are national security concerns.

In July 2025, the French government announced the forthcoming publication of the long-awaited Third Multiannual Energy Plan (“MEP”) which represents the French energy roadmap for the next ten years. Despite potential delays associated with the 2026 State Budget, it seems clear that the MEP will prioritise commissioning new nuclear power plants and ambitiously expanding renewables to reduce fossil fuel reliance.

These objectives require significant growth in decarbonised energy generation, and in the capacity of the transmission and distribution networks, which are currently operated under a form of monopoly, something which significantly limits private grid investment.

French state-owned utility EDF’s nuclear fleet – comprising 57 reactors with over 61 GW capacity – meets around 70% of France’s electricity demand. The next MEP is expected to confirm the construction of new EPR2-technology nuclear plants and support the promotion of small modular reactors.

It is also expected that the increasing use of renewable energy will continue. According to the French energy regulator (Commission de régulation de l’énergie), government subsidies for onshore and offshore wind, solar, and biogas are projected to reach a record €9 billion next year, after almost doubling in 2025. Ambitious MEP targets include 120 GW by 2030 and up to 190 GW by 2035. Offshore wind capacity is set to reach 18 GW by 2035 in the next MEP, leveraging France’s significant offshore wind potential.

We anticipate that France’s competitive electricity prices and low-carbon generation will continue to attract significant foreign investment in energy-intensive sectors such as AI, data centres, and giga-factories for batteries.

As can be seen above, the French energy sector is highly strategic and, before investing in France, foreign investors need to be aware that the French FDI regime is broad and covers acquisitions (including in some circumstances minority stakes) of French companies in strategic sectors that go beyond defence and security.

The French Monetary and Financial Code classifies investments subject to FDI into three categories, depending on the French target’s activities:

The materiality test is case-specific and inherently political, considering elements such as the type of customers (including operators of vital importance), applications and use cases of the products, know-how and systems/data, the hazardous/critical nature of certain products, or the target’s market position and the existence of any alternatives to its service/product.

In the context of energy transactions, important factors to consider are production capacity, local market share, the types of energy, the existence of alternative solutions with similar types of energy locally, and the impact on grid resilience or energy mix (in particular, location of production facilities can be important as overseas territories will be treated with caution).

The value of the transaction or the French target’s turnover are not, on their own, criteria which trigger a notification obligation but can be relevant in some cases. For instance, a very high value of transaction despite low revenues could indicate that the target owns a critical technology (see below).

In the context of energy investments, energy storage and low carbon energy production would be the main R&D activities captured under this heading by the French FDI regime.

In view of the above, energy investments would typically fall within in the second and third categories that require case-specific assessments. It is highly recommended to notify cases that would be deemed borderline, particularly in a politically sensitive sector such as energy.

Similarly to other European FDI regimes (but particularly common in France), approvals can be granted subject to conditions designed to mitigate any identified risks. Conditions that have been imposed to date include the following:

In the past three years there have been only six prohibition decisions under the French FDI regime across all sectors. In relation to the energy sector, in 2023 the Ministry of the Economy vetoed a proposed US acquisition of two French subsidiaries of a Canadian manufacturer and supplier of valves – which were supplied to French customers, operating in particular in the nuclear sector. While the valves were used in nuclear power plants, they were also installed on nuclear submarines – this played a key role in the decision and underlines the sensitivity of the wider nuclear sector in France.

By contrast, more than half of the authorisations granted in 2024 (excluding transactions deemed outside the scope of the FDI regime) were made conditional. Nuclear aside, this type of conditional approval can be considered more routine for acquisitions in the energy sector that involve elements of critical technology.

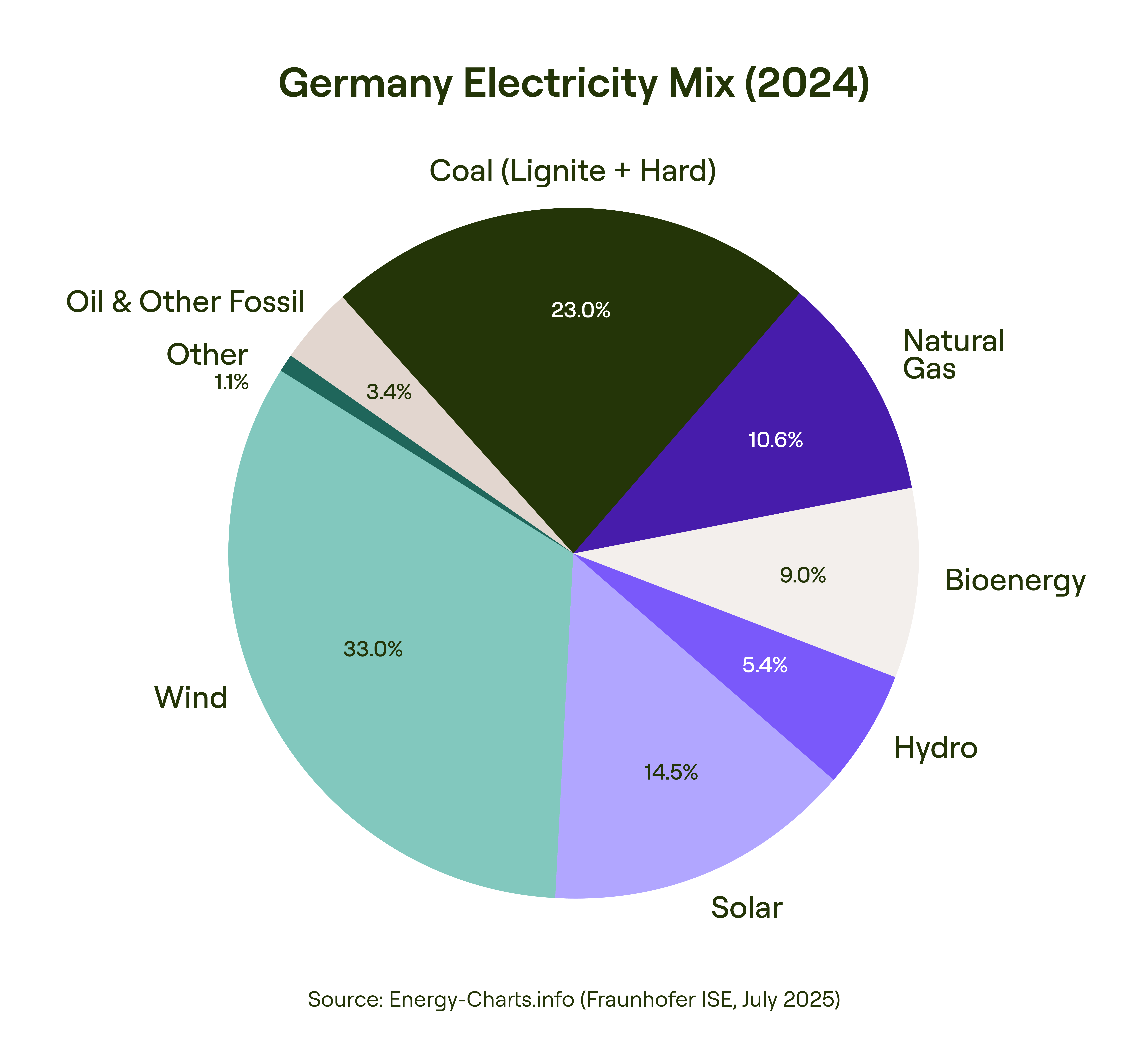

In Germany, the ‘trilemma’ of balancing decarbonisation, energy security (after years of heavy reliance on Russian gas), and affordability has become a defining challenge with far-reaching implications for investors and policymakers alike.

Against this backdrop, several regulatory developments and trends are currently shaping the German energy market.

In Germany, the energy sector has moved to the forefront of national security concerns. Policymakers view disruptions such as blackouts or deliberate sabotage of infrastructure as threats not only to the economy but also to public order. Another area of vulnerability is the potential loss of domestic industrial capacity: if key German companies fail and foreign – possibly adversarial – players dominate strategic sectors, Germany could become dependent on others for critical infrastructure, equipment, and services.

Germany’s investment screening regime is built on two key legal instruments: the Foreign Trade and Payments Act (AWG) and the Foreign Trade and Payments Ordinance (AWV). Together, they empower the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (“BMWE”) to review and, where necessary, block foreign acquisitions that threaten public order or national security.

Energy infrastructure is explicitly classified as “critical infrastructure” under German law, including operators that provide electricity or gas to more than 500,000 people. Since reforms in 2018, any non-EU investor acquiring 10% or more of a company operating such infrastructure must notify the BMWE. Importantly, transactions cannot be closed before clearance is granted. Breaches of this standstill obligation can render the deal legally void and may carry criminal penalties.

At present, greenfield investments – such as building a new wind farm or establishing a new energy subsidiary – are not subject to FDI screening, since no existing German entity is being acquired. However, there is ongoing political debate about expanding the regime to capture sensitive greenfield projects. Proposals for a dedicated Investment Screening Act are under discussion, which would represent a significant extension of Germany’s regulatory reach in this area.

Germany’s approach to investment screening has been shaped by several high-profile cases that illustrate how foreign ownership of critical assets can raise national security concerns, and these point towards certain trends:

These interventions show the broader set of tools Germany can deploy to retain control over critical infrastructure. They also demonstrate that even completed or longstanding foreign investments can become national security risks as the geopolitical environment shifts. These experiences have reinforced a more restrictive approach to FDI, with energy transactions linked to potentially hostile states now facing heightened scrutiny.

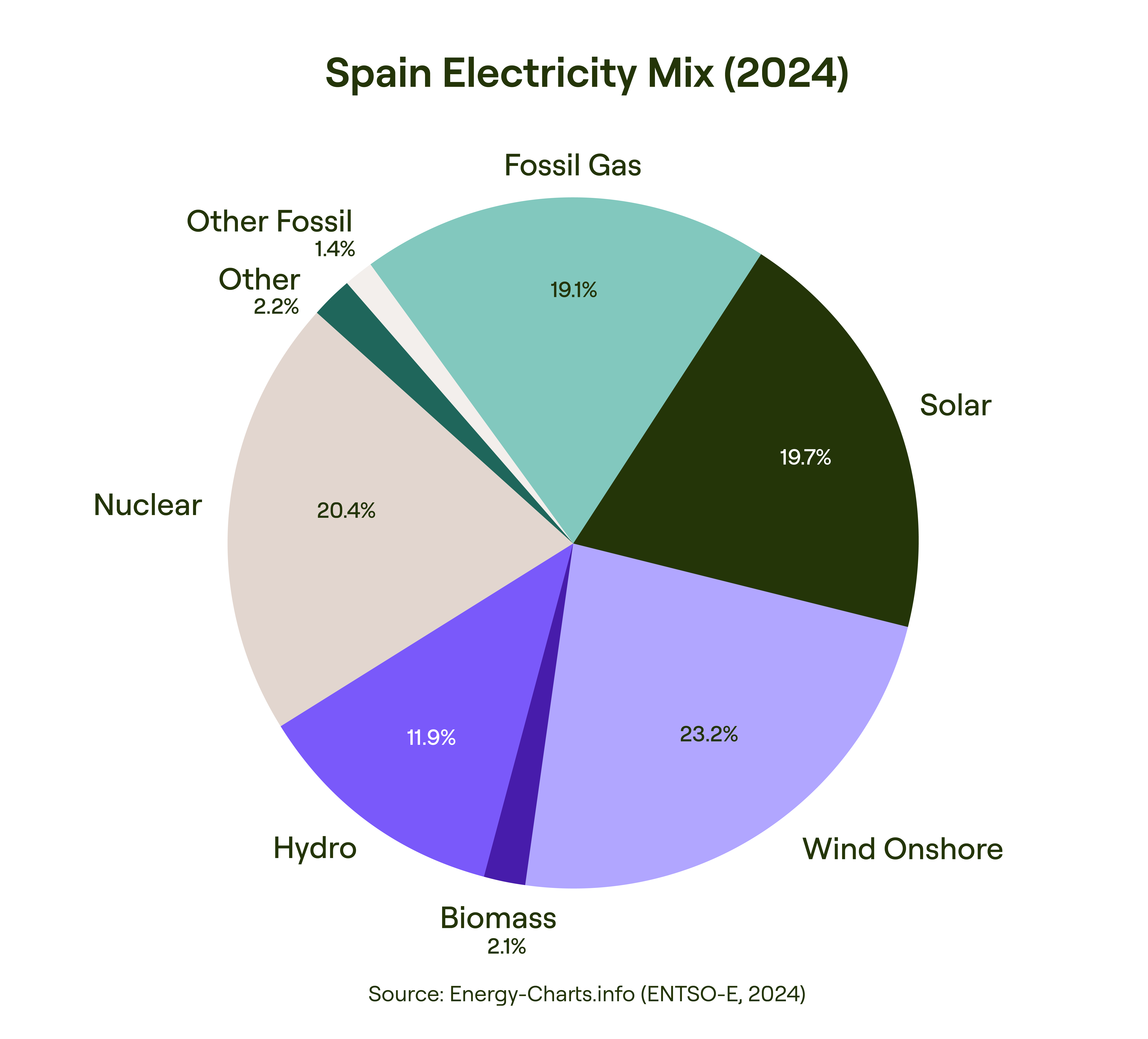

Spain is undergoing a profound energy transformation, guided by the National Integrated Energy and Climate Plan 2023–2030 (“PNIEC”), which sets ambitious goals for decarbonisation, efficiency, and security of supply. Key to this transformation will be boosting demand through major industrial and consumer projects.

The regulatory framework in Spain is structured around the Electricity Sector Law (2013) and the Hydrocarbons Law (1998), which define the organisation of the electricity and gas systems, respectively. Within this framework, the network operators – REE for electricity and Enagás for gas – act as transporters responsible for the construction and management of the transmission networks, and also as system operators tasked with ensuring coordination, security, and continuity of supply. At the same time, planning and authorisation of this infrastructure falls under the responsibility of State and autonomous communities. Finally, the National Commission on Markets and Competition (or CNMC) serves as the regulatory authority for the energy system, setting remuneration methodologies and conditions for network access, and ensuring the proper functioning of energy markets.

The emphasis on security of supply has become particularly relevant in light of the recent major blackout incident in Spain, which underscored the importance of grid resilience in a system with growing renewable penetration. As a result, there is a focus in Spain on the following objectives arising from recent legislation and reforms:

Spain’s FDI regime has undergone significant transformation in recent years, reflecting a broader shift toward economic security as a pillar of national security. This evolution has placed the energy sector – particularly electricity, gas, hydrocarbons, and critical infrastructure – at the centre of regulatory scrutiny.

The power blackout in April 2025, which disrupted power across peninsular Spain for up to 20 hours, has further intensified public scrutiny of energy infrastructure. The incident exposed vulnerabilities in grid stability, voltage control, and the integration of renewables. In response, the government proposed urgent reforms through Royal Decree-Law 7/2025, including enhanced oversight, hybrid storage prioritisation, and industrial electrification incentives. Although the decree was repealed amid political opposition, it reflects growing concern over energy system resilience and the strategic importance of infrastructure control.

The legal framework is anchored in Law 19/2003, as amended, and Royal Decree 571/2023, which together establish a general mandatory screening regime for foreign investments in sensitive sectors or when the investor falls within certain categories. The regime applies to investments where the foreign investor acquires at least 10% of a Spanish company or gains control through other means. While the regime primarily targets investors controlled from outside the EU or EFTA, it may also apply to EU/EFTA-based investors depending on the circumstances. Additionally, there is a separate authorization regime for investments related to national defence, which operates independently from the general screening framework (and is subject to lower thresholds and stricter requirements).

The energy sector is explicitly covered under the general regime (and potentially under the defence regime if related to national defence), with mandatory notification required for transactions involving any of the following:

The regime also provides narrowly defined exemptions for certain energy-related transactions, such as those involving non-regulated activities or where the investor’s market share remains below specific thresholds (e.g., less than 5% of installed generation capacity). However, these exemptions are interpreted narrowly and may not apply if the transaction intersects with other sensitive sectors beyond essential inputs/energy (e.g. critical infrastructure, relevant technologies, access to sensitive data etc.). Moreover, the Spanish government retains broad discretionary powers to review and potentially block transactions that could pose risks to public order, public safety, or national security.

The Spanish FDI authority, under the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Business, conducts detailed reviews of proposed transactions, focusing on the ownership of the investor (including links to foreign governments), the nature of the target’s assets and operations, and the impact on Spain’s energy supply, infrastructure resilience and strategic autonomy. The energy sector accounts for a significant share of the more than 400 FDI transactions reviewed since 2020 – reaching 20.8% of cases reviewed in 2024, making it the sector with the highest number of FDI transactions requiring approval.

Where risks are identified, the authority may impose conditions or even deny approval to safeguard national interests. Indeed, recent enforcement trends highlight the government’s willingness to intervene. In the energy sector, most interventions may result in conditional approvals, with commitments typically addressing issues such as the following:

Although the specifics of these decisions are rarely disclosed, recent cases in the energy sector demonstrate that authorisations may be granted with multiple conditions aimed at safeguarding strategic interests.

Spain’s FDI regime demonstrates a pragmatic approach, balancing national security with the need to attract investment and meet climate goals. However, the evolving regulatory landscape and geopolitical context mean that early legal risk assessment and proactive engagement with authorities are essential for investors in the energy sector.

The overarching challenge for governments around Europe – and indeed the world – is broadly the same: how do we produce affordable energy, which is secure and resilient, and works towards decarbonisation. How to achieve this, and exactly what this looks like for each country, is not straightforward and is not necessarily the same.

There are different national contexts, based on how energy supply and demand has evolved over decades in each of the UK, France, Germany and Spain, leading to a different mix of individual challenges. This informs the regulatory environment in each of these countries, and in turn the differing focus and emphasis in how each country’s FDI regime seeks to protect economic security as a core pillar of national security and public order.

Despite these differences – and significantly different energy mixes between countries – energy as a national security issue is a common thread which is woven into the FDI regimes of the UK, France, Germany and Spain. In response to this, we can identify certain themes which are common to each of these FDI regimes, despite nuanced details between countries. The key things which investors and business active in the energy sector need to consider are the following:

In this context, early engagement with regulators, robust legal assessments, and a clear understanding of FDI regimes are now essential components of successful energy investment strategies. Hogan Lovells operates at the cross-section of business of government and has detailed knowledge and extensive experience of navigating local, regional and international FDI regimes and energy markets. Please get in touch with our team if you would like to discuss any of the points raised in this article.

Authored by UK – Christopher Peacock, Stelios Charitopoulos, Karman Gordon, Johari Adjei, Inga Aryanova, Theo Cornish, Paul Sanderson; France – Victor Levy, Maxime Gardellin, Clément Marchaj; Germany – Philipp Reckers, Pia Heckenberger, Isabelle Baumgartner; Spain: Raquel Fernández, Casto González-Páramo, Teresa Vega de Seoane.